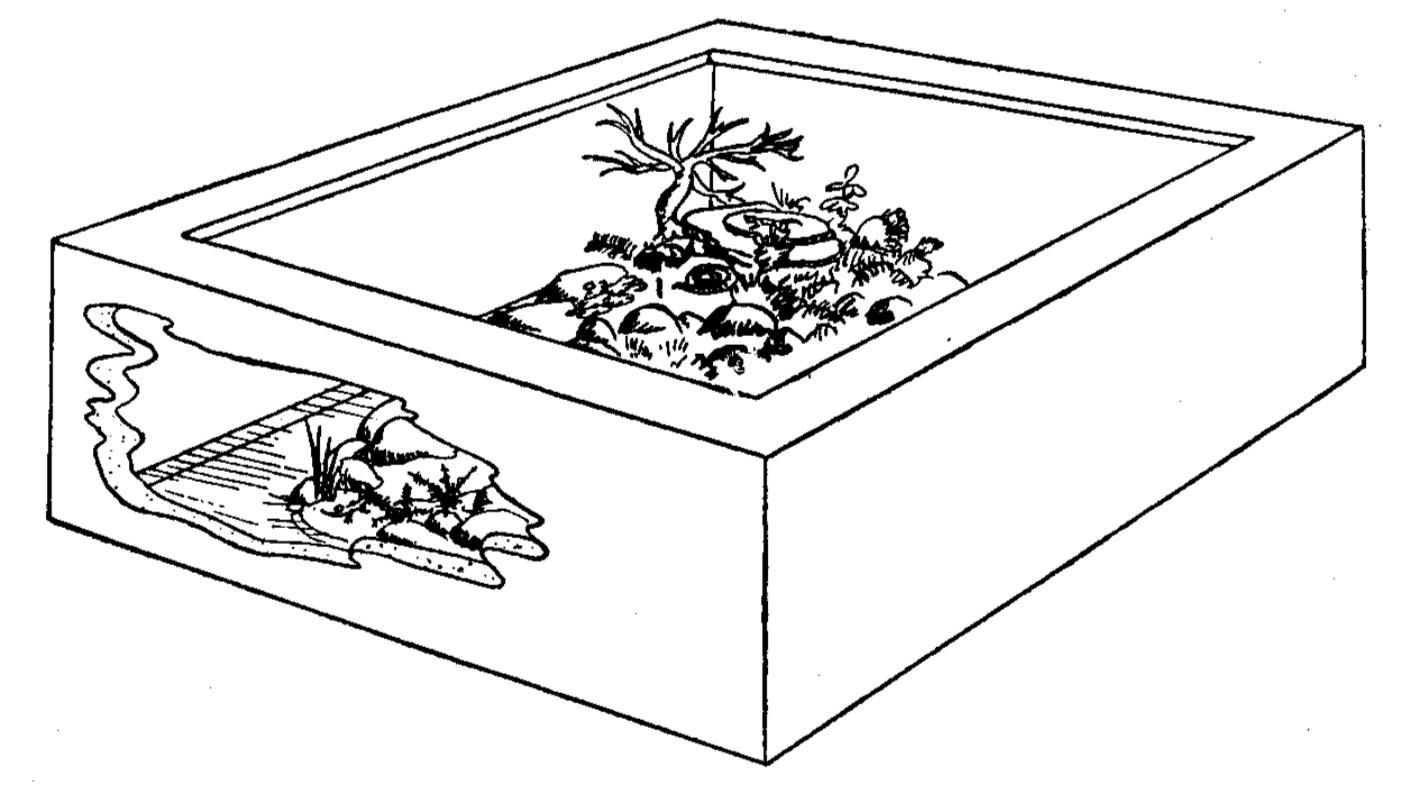

Once upon a time, when European lizards and snakes were imported into Britain, the dream of most amateur reptile keepers was to have an outdoor reptiliary in the garden—an enclosed but open space where lizards, snakes and amphibians could live a near-natural life.

I should begin by explaining that the reptiliary is sometimes referred to as a reptilium. However, the latter term had been used extensively for what we would now call a reptile house. The reptile houses in use before the present one at London Zoo were often referred to as the reptilium in press reports. The reptilium at Belle Vue, Manchester was a reptile house. However at Bristol Zoo, what we would now call an outdoor reptiliary was described as an outdoor reptilium. I wondered whether some classical scholar had been trying to avoid a barbarism, a mixture of Latin and Greek but since both words come from Latin roots that cannot be the reason. The extension of housing for birds by some, thus reptiliary, or of fishes by others, hence aquarium, may be the simplest explanation. And, yes, the barbarism, herpetarium, is also used for reptile house.

The early books on keeping reptiles carried no mention of the outdoor reptiliary. Yes, readers were told they could keep ordinary vivaria outside and one showed a photograph of a wired cage for lizards but no mention of what we now call a reptiliary.

The fashion to build a reptiliary, comprising a low wall with inward overhang complete with rockery and pond, seemed to follow the construction of the one at London Zoo in 1928. Like the Reptile House (1927) and the Main Gate the reptiliary was designed by Joan Procter, Curator of Reptiles. There was enormous media interest in the Zoo in the early decades of the last century and The Times (15 March 1930) describes it thus:

The outdoor Reptiliary near the Main Gate of the Zoo was devised to suit hardy reptiles from the colder parts of the world. The rockwork is placed over a core of dry, well-drained rubble with leaf mould, and the rocks were arranged so as to provide a number of deep recesses packed with mould. The deepest part of the pool contains nearly a foot of water under which is more than a foot of coherent mud. When the cold weather came, late last autumn, some of the lizards, snakes and terrapins continued to appear by day although the temperature was clearly too low for them. These were gradually gathered up and taken indoors. Others had found winter quarters to suit them, and it has been a great satisfaction to the Curator of Reptiles, who designed the Reptiliary, to find that these are now reappearing, none the worse for the winter.

The best photograph I have been able to find of the reptiliary was shown in The Illustrated London News of 15 September 1928. The Main Entrance in its original configuration can be seen behind. The caption indicates that the reptiliary was nearing completion which might suggest that it was first stocked in 1929.

Plants for the rockery were the responsibility of Clarence Elliott, a nurseryman. Twenty-five years later he wrote in The Illustrated London News:

When the open-air reptiliary was constructed at the London Zoo I was given the task of planting it and, among other things, I put in a young specimen of the twisted nut. With its fantastically serpentine stems it seemed to me particularly appropriate for this particular setting, and the tree has since grown into a magnificent specimen.

The tree, he explained, was a twisted (now usually called corkscrew) hazel.

An obituary of a plant collector, Edward K. Balls, suggests he, as an employee of Elliott, was involved in the construction of the rock garden as well as its planting. Elliott’s article, however, does indicate that they were only responsible for the planting.

During the Second World War, artists toured the country drawing and painting scenes which captured the sense of national identity, which may have been subject to loss by enemy action or by industrial or agricultural change. The scheme, ‘Recording the Changing Face of Britain’ was also intended to find employment and commissions for artists who might have found themselves out of work during war time. London Zoo’s reptiliary and main entrance was the subject of one such work by Walter John Bayes (1869-1956). The whole collection is now held by the Victoria & Albert Museum.

By Walter John Bayes. Recording Britain Collection, Victoria & Albert Museum

Were any changes made to the rockery over the lifetime of the reptiliary? David Lambert, with whom I have been corresponding on reptiliaries, recalls it being covered with more vegetation than shown in this photograph by Lionel Edward Hedley Day (1900-1968) that was published in Water Life in 1950. However, we do not know if the photograph was contemporary. Comparing that photograph with the one taken in 1928 (above) it would appear that it is from a position to the right. If that is the case then it would appear that the corkscrew hazel had been removed—before the time Elliott noted that it had ‘grown into a magnificent specimen’. My recollection from the late 1950s and early 1960s is that the whole rockery was lower. with large flattish areas covered by low plants. Does anybody have photographs from that time?

And in the Children’s Newspaper of May 23, 1959, Craven Hill wrote, “Officials at the Zoo are busy restocking the reptile rock garden…Gardeners have planted it with rock plants and arranged ‘sun cushions’—close growths of herbage on which the snakes and lizards can lie and sun themselves”.

What was kept in the reptiliary? We know from press reports that native Adders, Grass Snakes, Smooth Snakes were introduced. There is also mention of ‘Glass Snakes’, the legless lizard or Scheltopusik from eastern Europe. Aesculapian Snakes, Slow-worms, Green lizards, Wall Lizards’, ‘small lizards’, terrapins, tortoises and frogs are also listed. A snake reported to have hibernated successfully in the reptiliary was ‘a big dark-green snake’. That would be what is now known as Hierophis viridiflavus, from southern Europe. That snake got a mention in The Times of 15 March 1930:

A yellow cat, whose home is in one of the waiting rooms [in the main entrance?] had jumped on to the rockwork, possible in quest of sparrows, and was at once attacked with fury by the snake, which although not poisonous and far too small to make a prey of the cat made pussy cry out for help. Relief came in time.

The inhabitants of the reptiliary are listed in the 1935 guide to London Zoo:

The question of how long the Adders survived is difficult to answer. They were caught, along with Grass Snakes, in large numbers for London, other zoos and biological suppliers by a contractor in the New Forest. In the 1930s that was a Mr George Wateridge. The snakes were apparently used as food for King Cobras and other ophiophagous snakes as well as for some birds-of-prey. Whether this was so for Adders I do not know but it does seem clear that London and Edinburgh were topping up numbers of in their reptiliaries each year in what appear to be large quantities, for example, 60 to London, 48 to Edinburgh. Wateridge reckoned he sent 40 or more snakes to London every couple of weeks. Over-collection was attributed by some to the decline in snake numbers in the New Forest.

George Wateridge. Illustrated London News 22 July 1933. Note the astonishing caption: Making the New Forest Safe for Sightseers.

Various media reports suggest Wateridge like the snake catchers before him used a stick to pin the snake to the ground. Malcolm Smith in his New Naturalist series book stated that many Adders in captivity do not feed because this method of capture damages the gullet but that they then take many months to die. Whether that was an observation from the reptiliary at London is open to question. However, he did write: ‘In the large open-air reptiliary at the Zoo, where they live under fairly natural conditions, I have often watched them basking and moving about, and moving about, and sometimes feeding’.

Those still awake this far into the article will realise that the reptiliary housed lizards and frogs that are the normal prey of the snakes. Indeed, that may be the reason I never saw a lizard in the reptiliary in the late 1950s and early 1960s. I was always there in the late summer when a population of Adders could have worked its way through the lizards. I only ever saw Adders in there but what could be seen was so weather-dependent, an occasional visit could be entirely misleading as to the number and variety of animals.

That problem of a large reptiliary—predator and potential prey housed together— is only one of a number that became apparent over the years.

The first was predation. Newspapers reported that a small flock of Cattle Egrets released to fly free in London Zoo made very short work of the small lizards in the reptiliary. And might that ‘yellow cat’ have been searching out lizards rather than sparrows? Over the years, owners of reptiliaries have been plagued by cats, gulls, crows and the like necessitating the use of some sort of cover. The aesthetic appeal of an open-air enclosure is thus compromised.

The second problem for London was litter. The public loved to feed zoo animals and the offerings tossed over the wall for the inhabitants of the reptiliary may have been choice items for monkeys but not for lizards or snakes. Regular patrols had to remove peanuts, biscuits, bread crumbs and cake.

The third was safety. The reptiliary had no bounding fence just the low wall that can be seen in the photographs. A child clambering on the wall could—and probably did—tumble onto the inside. The consequences of landing on an Adder may not have been pleasant. The job of refurbishing the reptiliary (as in the 1959 replanting by gardeners) must have been seen as a challenge. Finding every last one of the venomous snakes in the deep recesses of rockwork and underground cavities cannot have been easy. Perhaps so many rocks had to be shifted that the original configuration was not maintained and that I really do remember a lower structure in the early 1960s.

The fourth was security. It is now well known that small boys could push their way through the boundary fence of the Zoo on a light evening and search the reptiliary for a grass snake or terrapin to take home.

I suspect that by the early 1960s the Zoo had pretty well given up on the reptiliary. I remember talking to Reg Lanworn (1908-2005), resplendent in his uniform of Overseer of Reptiles, one afternoon when I, still at school, went to ask him something about reptiles. We were beside the reptiliary and he indicated that stocking it was not seen as a priority. I also suspect that the annual topping up from the relatively large numbers of reptiles imported by dealers from Italy each spring had ended.

The reptiliary was demolished in 1970 as the area around the old Monkey House was reconfigured for the Sobell primate house. Angus Bellairs and David Ball in their article for the 150th anniversary of the Zoo in 1976 wrote: ‘The practice of keeping European reptiles in an outdoor reptiliary was abandoned some years ago for various reasons’.

But later and potentially confusingly another enclosure became known as the reptiliary in Guillery’s The Buildings of London Zoo (1993). This was the 1922 Otter Pond which housed various animals until it was converted for iguanas. That too now seems to have been demolished.

Other zoos in the 1930s

A number of zoos in Britain soon acquired outdoor reptiliaries. Bristol had one (‘outdoor reptilium’) in 1930. Belfast announced one was in its plans for construction before the zoo opened in 1934. Edinburgh had one by 1937 (when it received Adders from the New Forest); Zoo magazine, later Animal & Zoo Magazine, shows it was built in 1936 and was of the London design with two streams of which one ran into a marsh. The reptiliary at Dudley Zoo was built in 1935-37 in time for the zoo’s opening in 1937. That one is relatively safe from destruction since it has a Grade II conservation listing but it hasn’t held reptiles for decades. It now holds the ubiquitous Meerkat. The reason for its conservation (albeit in bastardised form) is that it was designed (actually pretty much a straight copy of Joan Procter’s) by Lubetkin/Tecton, along with the other Tecton buildings which made Dudley so distinctive. The main adviser to Dudley was Geoffrey Vevers, Superintendent of London Zoo so it is not surprising that Lubetkin, after his iconic (but ultimately wrongly-designed for sub-antarctic species) Penguin Pool and what turned out to be an utterly useless Gorilla House at London, was given the job.

The reptiliary at Dudley can be seen clearly on Google Earth. I must have looked in the first time I visited Dudley in 1954 and in my second and only other visit about five years later but I have no recollection of having done so.

The outline of the reptiliary at Dudley Zoo (adjacent to the later Reptile House)can be seen in this view from Google Earth.

Then Whipsnade had a reptiliary in 1938. Syndicated media reports suggest a London-style structure:

A rock garden, surrounded by a moat, is being built, and it is said to be the hime of the hardy reptiles, such as common adders, grass snakes, slow-worms, and wall lizards, as well as common frogs. There will be no bars separating the exhibits from the public, but the moat will be banked by a parapet, deeply curved on the inner side, so that the snakes cannot climb out.

In the next article I will try to draw together the experiences of amateur herpetologists in building and maintaining a garden reptiliary.

Before I do that I should point out that in the tropics the snake pit was the norm. Below are photographs we took at the Bangkok Snake Farm in 1968. I do wonder whether the idea of a reptiliary at London came from Dr Malcolm Smith who returned from Thailand where was physician to the royal court in 1925. The snake farm, part of the Queen Saovabha Memorial Institute for the production of antivenoms, opened in 1923. Smith was a close collaborator of G.A. Boulenger, Joan Procter’s mentor at the British Museum.

Bellairs Ad’A. 1976. Reptiles. In, The Zoological Society of London 1826-1976 and Beyond. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 40, 119-132.

Chalmers Mitchell P. 1935. Official Guide to the Gardens and Aquarium of the Zoological Society of London. 32nd edition. London: Zoological Society of London

Guillery P. 1993. The Buildings of London Zoo. London: Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England.

Smith M. 1954. The British Amphibians & Reptiles. Revised edition. London: Collins.

Amended 7 May 2019 and 3 June 2019